Gennaio 8, 2026

From Puzzle to Passkey: Physical Authentication Through Rubik’s Cube Scrambles

Dicembre 12, 2025

Novembre 17, 2025

La poligrafia dell’FBI e dei Servizi statunitensi. Il metodo della Probable Lie Comparison.

The FBI polygraph is a variant of the Department of Defense Law Enforcement Pre-Employment Test (LEPET). The specific technique used is the Probable Lie Comparison Test (PLC), in which the examinee is asked question on which he is expected to lie, in order to compare his reaction to his reaction to relevant questions. For a more comprehensive and detailed discussion of the LEPET, please refer to the LEPET briefing booklet.

The FBI polygraph is intended to give the FBI important information about you for use throughout the hiring process. First, it is an assessment of your honesty, because you have to answer every question truthfully. In addition to automated scoring software, a polygraph specialist Supervisory Special Agent at headquarters will carefully study your charts. If any deception is indicated, you fail. If no deception is indicated, you pass.

Second, the polygraph examination helps determine your suitability by ensuring that you have disclosed all drug-related and crime-related information. Third, the examination ensures that you have provided truthful information elsewhere in your application process. Fourth, the examination establishes your loyalty to the United States. Unless otherwise stated, the examination covers only the period of your life since you turned 18 years old.

When the examiner and I walked into the room, he instructed me to sit in the chair at the top left of the diagram. He carefully positioned me in the chair so that I was directly facing him. At this point I noticed a large area of one way glass on the opposite wall. The examiner started talking to me about basic information to build rapport, as outlined in the DOD LEPET briefing booklet. Then he hit me with a surprise; “for every twelve hundred applicants, only one gets to sit where you’re sitting now.” My jaw dropped. Then I was confused; I calculated in my head the number of Special Agent applicants and concluded this was not possible. I later learned that my exam was mistakenly scheduled as a “support” applicant rather than as a Special Agent applicant. For support applicants, his figures would still not make sense despite the hiring “surge” that year.

The pre-test interview continued in accordance with the LEPET manual. My favorite part was, “on a scale of one to ten, how do you rate your honesty?” I said nine. He then asked, “what level of honesty do you think the FBI should require?” I said nine. He said that some people give themselves a lower value of honesty than they believe the FBI should hire. I laughed and said “why would anyone do that?” He just smiled. These questions were used to establish my baseline levels for different emotional responses. The funny thing was, the examiner wasn’t looking at me that carefully as he asked me these introductory questions. Based on this and the presence of one-way glass, I conclude that an observer was watching me carefully and that polygraph examiners and their assistants are trained to read subtle expressions and/or microexpressions, not just body language like the rest of the FBI. For example, a psychopath liar may carefully watch the person he is lying to to see whether they notice the lie. Or, when lying, a psychopath may show “duping delight” because he enjoys deceiving others. (…)

The interview continued with what the examiner described as the “Robert Hanssen questions.” Interestingly, he asked who in my family taught me not to lie. He said “your Dad?” I said both of my parents taught me not to lie. He followed that with “and your teachers?” Yes. We talked about my personal background, like where I grew up. He asked whether I’d ever been married or divorced. He asked whether I had been a partner in the law firm I used to work for. He then explained how the examination works. There would be no “surprise questions.” There would be a series of practice questions during which the “instrument” was off, and then the same questions would be asked with the instrument turned on. I would have the opportunity to clarify any issues with the questions during the practice questions, so that we both understood and so there were no miscommunications.

The examiner asked whether I knew anything about the polygraph. I told him I read the Wikipedia page on polygraph examinations except for the part about countermeasures. He said words to the effect of “well, we have a very sensitive instrument here that will detect any countermeasures, so there would be no point in trying to use them anyway.”

(…) I passed his questions, filled out a consent to polygraph form, and the examination began. He hooked me up to the machine by placing a finger on my left hand into a galvanic skin response device, placing a heated gel pad under my left hand, fitting me with a blood pressure type cuff, wrapping flexible plastic tubes around my torso, and telling me how to sit in the chair properly. The polygraph chair looks like a cross between a dentist’s chair and the electric chair. The chair has arm, seat, and feet movement sensors hooked up to the instrument.

The video camera was in the top corner of the wall pointed at me, but I didn’t ask and he didn’t say whether it was on. I don’t recall the examiner announcing anything for the video camera like case number, start time, etc. He could have done this before I got there. Given that some examinations are multiple hours, it would make sense to only videotape the most important national security examinations or cases involving serious crimes. I don’t know.

Because I have concluded that lawyers are singled out for especially negative treatment in the process, and because the DOD LEPET booklet contains sample relevant questions that are publicly available and nearly identical to the ones used by the FBI, I have decided to disclose all of the questions I can remember during the examination. Anyone who can demonstrate how this might be improper is invited to do so.

The examiner wrote out a series of numbers and explained that he would test my reactivity by asking me a question that would prompt a “known lie.” He taped the sheet of paper on the blank wall in front of me. “Look straight ahead at the list of numbers on the wall. The lie will be when you tell me that the number in the box is not the number six. I am now turning on the instrument. Is the number one in the box?” No. “Is the number two in the box?” No. “Is the number three in the box?” No. “Is the number four in the box?” No. “Is the number five in the box.” No. “Is the number six in the box?” No. “Is the number seven in the box?” No. “OK, we have a textbook reaction on that one, now we can begin.” I thought to myself, “oh shit, that is a really sensitive machine.” [The reaction occurs not when the “lie” is told, but occurs when the examinee thinks, “oh shit, that is a really sensitive machine!”]

Attorney-specific series

“Have you ever lied to or misled a client?” No [mild reaction–I felt my gut tensing up].

“Have you ever represented your assumption of a client’s belief as fact?” No.

“Have you ever falsified a record of continuing legal education?” No.

“Have you ever overbilled a client?” No.

“Do you intend to lie to me today?” No.

“Have you ever gossiped about people?” No.

“Were you lying to me earlier when you rated yourself a nine on the scale of honesty?” No [mild reaction–afraid I overstated my honesty].

“Have you ever contributed to an organization that finances terrorism?” No.

Relevant Questions (the ones I’m sure about):

“Have you disclosed all of the information you have concerning your use of illegal drugs?” Yes.

“Have you ever committed a serious crime?” Yes. [Machine was off–practice question] “What serious crimes have you committed?” Just what’s in my application–lying on a parking permit application and pirating software in college. “No, I’m not referring to what is disclosed in your written application, those are not serious crimes. Serious crimes are, for example, murder, rape, assault and battery, shoplifting as an adult, and other crimes of that nature. Have you ever committed any serious crimes?” No. [Machine goes on]. “Other than what you’ve told me about, have you ever committed a serious crime?” No.

“Are all of the statements in your application truthful?” Yes.

“Have you ever committed an act of espionage?” No.

“Is your name [John Doe]?” Yes.

The questions above are out of order; I don’t remember the exact sequence. Refer to the LEPET booklet for information on sequencing and “priming” of the examinee.

After the first series of questions was asked, the examiner took the heated pad from under my left hand and went in the back room. He returned a couple of minutes later and replaced the pad under my hand. It was a lot warmer. I conclude he microwaved it for the prescribed amount of time to induce sweating in my left hand, which was bone dry at that point.

The post-test interview is an opportunity for the examinee to explain any reactions made on the test. If the reactions are to comparison questions and the examinee explains his reaction sufficiently, no further testing is done. For example, in my case I knew I reacted to the question “have you ever lied to or misled a client?” I told the examiner that my boss told me not to tell two particular clients bad news over the phone, but instead to have them come in personally. The clients asked me, over the phone, what I thought about a recent event in their case. I asked them to come in to discuss it. I told the examiner that I wanted to tell them the bad news over the phone, but I couldn’t disobey my boss, and that it wasn’t lying because they were going to come in personally. That resolved the issue. I also reacted to the question “were you lying to me when you rated yourself a nine on the scale of honesty?” I told the examiner I was afraid that I overestimated my honesty. There was no concern. The examiner told me that he didn’t see anything in particular that was outside of acceptable parameters, but that headquarters would make the final decision. The whole process took an hour and the exam itself was forty-five minutes.

If the examinee reacts to relevant questions, further “breakdown” testing is done to explore those areas. Had I reacted to the relevant question “have you ever committed an act of espionage,” the question would be broken out into the elements of espionage: “have you ever had access to classified information?” “Have you ever disclosed classified information to an agent of a foreign power?” “Have you ever lost or misplaced classified information?” “Have you ever failed to report espionage activity you knew of?” And so on. The LEPET booklet is really helpful in understanding this area of questioning. In my case no breakdown questioning was necessary. The examiner’s last words to me on the way out were, “it was a pleasure meeting you. Truly.”

My polygraph was easy, because I had nothing to hide and there is nothing dramatic in my background. Here is the report. After considering all of the factors and my experience, I cannot possibly imagine “beating the machine.” To do so would probably involve tranquilizers plus classified training from the CIA, or a psychopathic personality disorder in which the examinee actually believes he is telling the truth when he is lying, or doesn’t care. In other words, Hannibal Lecter or Aldrich Ames. Ames caused the deaths of a number of American-run agents in the Soviet Union so that he could avoid being caught. I mean, seriously. Hopefully people who can beat the machine get filtered out with the biodata inventory at Phase I or in the background investigation. [Aldrich Hazen Ames (born May 26, 1941) is an American former CIA counterintelligence officer who was convicted of espionage on behalf of the Soviet Union and Russia in 1994. He is serving a life sentence, without the possibility of parole, in the Federal Correctional Institution in Cumberland, Maryland. Ames was known to have compromised more highly classified CIA assets than any other officer until Robert Hanssen, who was arrested seven years later in 2001.]

[The Employee Polygraph Protection Act of 1988 (EPPA) is a United States federal law that generally prevents employers from using polygraph (lie detector) tests, either for pre-employment screening or during the course of employment, with certain exemptions.Under EPPA, most private employers may not require or request any employee or job applicant to take a lie detector test, or discharge, discipline, or discriminate against anybody for refusing to take a test or for exercising other rights under the act. However, the act does permit polygraph tests to be administered to certain applicants for job with security firms (such as armored car, alarm, and guard companies) and of pharmaceutical manufacturers, distributors, and dispensers. The law does not cover federal, state, and local government agencies.]

Novembre 3, 2025

A police officer’s first year in South Central, Los Angeles, 1996

William Carl Dunn. Boot: An LAPD Officer’s Rookie Year. William Morrow and Company, 1996

Settembre 23, 2025

Luglio 9, 2025

Gender without Gender Identity: The Case of Cognitive Disability. Elizabeth Barnes

What gender are you? And in virtue of what? These are questions of gender categorization. Such questions are increasingly at the core of many contemporary debates about gender, both within philosophy and in public discourse.

Growing efforts are being made to highlight the importance of gender identity to gender categorization. Philosophical theories of gender have traditionally focused on gender role—the social norms, obligations, and positions that others impose on you based on perceived gender. But the experiences of trans, non-binary, and gender nonconforming people have shown that an exclusive focus on gender role is inadequate for theorizing gender. We also need to consider a person’s relationship to gender categories and gender norms. Two people might both be perceived by others as women, but while one thinks of herself as a woman the other thinks of themself as genderqueer. And this difference in gender self-identification is not merely a difference in personal feeling. A gender nonconforming woman and a genderqueer person—even if they are treated similarly by others—will often experience and navigate gender norms and roles quite differently, and this difference matters to a full understanding of gender.

In what follows, I am by no means attempting to dispute that gender identity is an important aspect of gender and gender categorization. Rather, I’m going to argue that we shouldn’t swing the pendulum too far the other way. It’s become increasingly common, in both popular and philosophical explanations of gender, to claim that gender identity uniquely determines one’s gender, that is, that gender categorization is solely a matter of gender self-identification. That, I’ll argue, is too strong. While gender identity matters, it isn’t the sole determinant of gender.

Identity-based views of gender categorization put a cognitive requirement on gender membership. One must identify as gender x in order to be classed as gender x. Identifying as gender x, at least on extant philosophical theories of gender identity, is a matter of complex social reasoning and self-understanding. It requires awareness of various social norms and roles (and, moreover, an awareness of them as gendered), the ability to articulate one’s own relationship to those norms and roles, and so on. But many cognitively disabled people have little or no access to language. Many tend not to understand social norms, much less to identify those norms as specifically gendered. And many lack the type of social and interpersonal awareness to be able to make judgements about their own ‘sense of gender’. This won’t, of course, be the case for all cognitively disabled people, and it’s important to acknowledge that there is a wide range of cognitive and social experiences that fall within the broad heading ‘cognitive disability’. In what follows, I don’t mean to paint all cognitively disabled people with the same broad brush, or to assume that all cognitively disabled people are incapable of having a strongly felt sense of gender self-identification. One only needs to look, for example, at the vibrant drag culture among some people with Downs Syndrome to see how richly some people with cognitive disabilities experience gender via self-expression and self-identification.

But the wide range of cognitive disability—and the specific ways in which cognitive disability can affect social understanding and social reasoning—make it plausible that many cognitively disabled people simply don’t have this type of highly developed sense of their own.

Elizabeth Barnes, Gender without Gender Identity: The Case of Cognitive Disability, Mind, Volume 131, Issue 523, July 2022, Pages 838–864, https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/fzab086

https://philarchive.org/rec/BARGWG

Giugno 30, 2025

Giugno 25, 2025

The worthwhile problems are the ones you can really solve. Da una lettera di Richard Feynman

Dear Koichi,

I was very happy to hear from you, and that you have such a position in the Research Laboratories. Unfortunately your letter made me unhappy for you seem to be truly sad. It seems that the influence of your teacher has been to give you a false idea of what are worthwhile problems. The worthwhile problems are the ones you can really solve or help solve, the ones you can really contribute something to. A problem is grand in science if it lies before us unsolved and we see some way for us to make some headway into it. I would advise you to take even simpler, or as you say, humbler, problems until you find some you can really solve easily, no matter how trivial. You will get the pleasure of success, and of helping your fellow man, even if it is only to answer a question in the mind of a colleague less able than you. You must not take away from yourself these pleasures because you have some erroneous idea of what is worthwhile.

You met me at the peak of my career when I seemed to you to be concerned with problems close to the gods. But at the same time I had another Ph.D. Student (Albert Hibbs) was on how it is that the winds build up waves blowing over water in the sea. I accepted him as a student because he came to me with the problem he wanted to solve. With you I made a mistake, I gave you the problem instead of letting you find your own; and left you with a wrong idea of what is interesting or pleasant or important to work on (namely those problems you see you may do something about). I am sorry, excuse me. I hope by this letter to correct it a little.

I have worked on innumerable problems that you would call humble, but which I enjoyed and felt very good about because I sometimes could partially succeed. For example, experiments on the coefficient of friction on highly polished surfaces, to try to learn something about how friction worked (failure). Or, how elastic properties of crystals depends on the forces between the atoms in them, or how to make electroplated metal stick to plastic objects (like radio knobs). Or, how neutrons diffuse out of Uranium. Or, the reflection of electromagnetic waves from films coating glass. The development of shock waves in explosions. The design of a neutron counter. Why some elements capture electrons from the L-orbits, but not the K-orbits. General theory of how to fold paper to make a certain type of child’s toy (called flexagons). The energy levels in the light nuclei. The theory of turbulence (I have spent several years on it without success). Plus all the “grander” problems of quantum theory.

No problem is too small or too trivial if we can really do something about it.

You say you are a nameless man. You are not to your wife and to your child. You will not long remain so to your immediate colleagues if you can answer their simple questions when they come into your office. You are not nameless to me. Do not remain nameless to yourself – it is too sad a way to be. now your place in the world and evaluate yourself fairly, not in terms of your naïve ideals of your own youth, nor in terms of what you erroneously imagine your teacher’s ideals are.

Best of luck and happiness. Sincerely, Richard P. Feynman.

http://genius.cat-v.org/richard-feynman/writtings/letters/problems

Giugno 23, 2025

L’Orlando furioso. Le penne e i destrieri

La bella donna tuttavolta priega

ch’invan la dura squama oltre non pesti.

— Torna, per Dio, signor: prima mi slega

(dicea piangendo), che l’orca si desti:

portami teco e in mezzo il mar mi anniega:

non far ch’in ventre al brutto pesce io resti. —

Ruggier, commosso dunque al giusto grido,

slegò la donna, e la levò dal lido.

(…)

Quivi il bramoso cavallier ritenne

l’audace corso, e nel pratel discese;

e fe’ raccorre al suo destrier le penne,

ma non a tal che piú le avea distese.

Del destrier sceso, a pena si ritenne

di salir altri; ma tennel l’arnese:

l’arnese il tenne, che bisognò trarre,

e contra il suo disir messe le sbarre.

Frettoloso, or da questo or da quel canto

confusamente l’arme si levava.

Non gli parve altra volta mai star tanto;

che s’un laccio sciogliea, dui n’annodava.

Ma troppo è lungo ormai, Signor, il canto,

e forse ch’anco l’ascoltar vi grava:

si ch’io differirò l’istoria mia

in altro tempo che piú grata sia.

Orlando furioso. Canto X. 111-115.

Giugno 15, 2025

Giugno 12, 2025

La solitudine

La solitudine – a volerla debitamente definire – è di tre tipi: del luogo …; del tempo, ovverosia delle notti, quando anche nel foro c’è solitudine e silenzio; dell’animo, ovverosia di quelli che, per la straordinaria capacità di concentrarsi nella contemplazione, si sottraggono al mezzogiorno e alla piazza affollata e ignorano che cosa vi succeda e sono soli in qualunque momento e luogo vogliano esserlo. (…)

Francesco Petrarca. De vita solitaria.

Giugno 11, 2025

Natural Semantic Metalanguage (NSM)

The Natural Semantic Metalanguage approach, originated by Anna Wierzbicka, can lay claim to being the most well-developed, comprehensive and practical approach to cross-linguistic and cross-cultural semantics on the contemporary scene. It has been applied to over 30 languages from many parts of the world.

The NSM approach is based on evidence that there is a small core of basic, universal meanings, known as semantic primes, which can be expressed by words or other linguistic expressions in all languages. This common core of meaning can be used as a tool for linguistic and cultural analysis: to explain the meanings of complex and culture-specific words and grammatical constructions (using semantic explications), and to articulate culture-specific values and attitudes (using cultural scripts). The theory also provides a semantic foundation for universal grammar and for linguistic typology.

Using NSM allows us to formulate analyses which are clear, precise, cross-translatable, non-Anglocentric, and intelligible to people without specialist linguistic training.

The method has applications in intercultural communication, lexicography (dictionary making), language teaching, the study of child language acquisition, legal semantics, and other areas.

(Griffith University)

https://intranet.secure.griffith.edu.au/schools-departments/natural-semantic-metalanguage

Giugno 3, 2025

Trickle up economics. La mafia penitenziaria

The Black Hand: The Bloody Rise and Redemption of “Boxer” Enriquez, a Mexican Mob Killer. Chris Blatchford (2009)

Maggio 29, 2025

How to Do Soul-Craft with State Tools. On Literacy and AI

Widespread literacy… is not a natural baseline but a costly ecological accomplishment. It depends on sustained, large-scale societal investment in both cultivation and maintenance. If that investment falters—or if new modes of communication arise that are less cognitively demanding and more closely aligned with our oral-auditory predispositions—then this hard-won literate ecology can erode rapidly.

In other words, mass literacy is not simply a skill that might fade. It is a complex cognitive adaptation—difficult to build, easy to displace—and, if outcompeted, literacy may once again become the province of a specialized elite.

Historically, we accepted literacy’s steep training cost because it offered a unique bundle of symbolic affordances: durable storage, precise retrieval, spatialization, and combinability. These were not luxuries— they were prerequisites for disciplines like law, science, literature, and philosophy.

Now, AI-mediated oral-auditory systems provide many of those same affordances—cloud memory, instant query, spatialized workspaces, speech-to-anything translation—at a fraction of the acquisition cost. We do not need ten years of schooling to learn to ask a language model, by voice, to store or retrieve language.

If new media outperform text on primary utility, ordinary selection pressure may displace literacy from its cultural and cognitive niche. But while these systems may replicate many of the affordances of textuality, their effects may be fundamentally different. And when it comes to literacy, it is precisely the secondary and tertiary effects that carry disproportionate value.

These effects include recursive empathy, long-horizon abstraction, disciplined counterfactual reasoning, interiority, and the capacity to entertain multiple perspectives over time. They emerge slowly, through sustained symbolic engagement. They are difficult to measure, easy to overlook, and prone to erosion when unattended.

To be clear about the mechanism: our society selects for the affordances of a medium—speed, ease, efficiency—not for its effects. And it is the effects of literacy that hold its civilizational value. This is the critical point: those deep cognitive and ethical capacities are not being selected for. They are not easily monetized or optimized. They rarely register on the dashboards that guide decision-making.

Jac Mullen

https://jacmullen.substack.com/p/before-and-after-literacy

Maggio 28, 2025

The Formal Structure(s) of Analogical Inference. Filosofi al Politecnico delle Marche

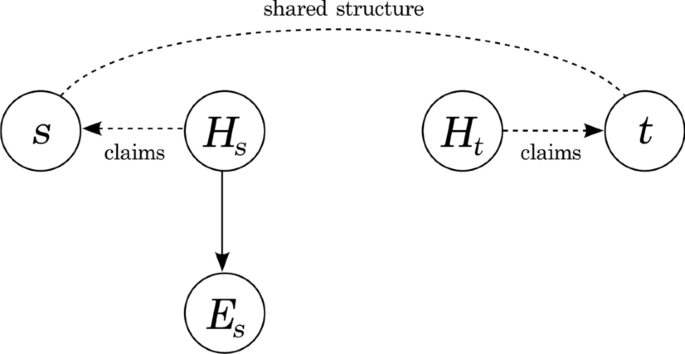

Recently, Dardashti et al. (Stud Hist Philos Sci Part B Stud Hist Philos Mod Phys 67:1–11, 2019) proposed a Bayesian model for establishing Hawking radiation by analogical inference. In this paper we investigate whether their model would work as a general model for analogical inference. We study how it performs when varying the believed degree of similarity between the source and the target system. We show that there are circumstances in which the degree of confirmation for the hypothesis about the target system obtained by collecting evidence from the source system goes down when increasing the believed degree of similarity between the two systems. We then develop an alternative model in which the direction of the variation of the degree of confirmation always coincides with the direction of the believed degree of similarity. Finally, we argue that the two models capture different types of analogical inference.

Gebharter, A., Osimani, B. The Formal Structure(s) of Analogical Inference. Erkenntnis (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-025-00934-8

(Center for Philosophy, Science, and Policy, Marche Polytechnic University)

Maggio 24, 2025

Characterization of an adaptive logic

The adaptive logic programme aims at developing a type of formal logics (and the connected metatheory) that is especially suited to explicate the many interesting dynamic consequence relations that occur in human reasoning but for which there is no positive test (see the next section). Such consequence relations occur, for example, in inductive reasoning, handling inconsistent data, …

The explication of such consequence relations is realized by the dynamic proof theories of adaptive logics. These proof theories are dynamic in that formulas derived at some stage may not be derived at a later stage, and vice versa.

The programme is application driven. This is one of the reasons why the predicative level is considered extremely important, even if, for many adaptive logics, the basic features of the dynamics are already present at the propositional level. The main applications are taken from the philosophy of science; some also from more pedestrian contexts.

Much interesting actual reasoning displays two forms of non-standard dynamics.

- An external dynamics: a conclusion may be withdrawn in view of new information. This means that the consequence relation is non-monotonic.

- An internal dynamics: a conclusion may be withdrawn in view of the better understanding of the premises provided by a continuation of the reasoning.

While examples of logics displaying the external dynamics are available, logicians did not pay much attention to the internal dynamics. And yet it is very familiar to anyone. Reasoning from one’s convictions, one often derives a consequence that one later rejects, even if one’s convictions were not modified. The point is that humans are unable to see at once all the consequences of a set of premises (in this case, one’s convictions).

To clearly understand the two forms of dynamics, it is useful to compare them to the standard forms of logical dynamics. These are common to all reasoning, and well known from usual logics. First consider the standard external dynamics. If we are reasoning (by some logic L) from a set of data  and, at some point in time, are supplied with a supplementary set of data

and, at some point in time, are supplied with a supplementary set of data  ‘, we are in general able to derive more consequences from that point in time on. Formally: CnL(

‘, we are in general able to derive more consequences from that point in time on. Formally: CnL( )

)  CnL(

CnL(

’). Next consider the standard internal dynamics. Given a set of rules of inference, not all formulas derivable from a set of premises are derivable by a single application of a rule at some stage of a proof. The set of formulas derivable by a single application of a rule monotonically increases as the proof proceeds. A different form of dynamics is related to the fact that humans are unable to see at once all the consequences of a set of premises. As a result, some statements will only be seen to be derivable from the premises after other statements have been derived. The derivability of a statement, however, does not depend on the question whether one sees that it is derivable. So, this form of internal dynamics is related to logical heuristics and to computational aspects, rather than of the logic properly. To be more precise: the formulation of the proof theory is fully independent of it. As we shall see later, the matter is completely different for consequence relations that display an adaptive internal dynamics.

’). Next consider the standard internal dynamics. Given a set of rules of inference, not all formulas derivable from a set of premises are derivable by a single application of a rule at some stage of a proof. The set of formulas derivable by a single application of a rule monotonically increases as the proof proceeds. A different form of dynamics is related to the fact that humans are unable to see at once all the consequences of a set of premises. As a result, some statements will only be seen to be derivable from the premises after other statements have been derived. The derivability of a statement, however, does not depend on the question whether one sees that it is derivable. So, this form of internal dynamics is related to logical heuristics and to computational aspects, rather than of the logic properly. To be more precise: the formulation of the proof theory is fully independent of it. As we shall see later, the matter is completely different for consequence relations that display an adaptive internal dynamics.

Many consequence relations are undecidable and the predicative versions of nearly all logics are undecidable. If a logic is undecidable but monotonic, there still may be a positive test for derivability. However, if a consequence relation is undecidable and non-monotonic, there can only be a positive test for it in some rather artificial cases. There may at best be a definition of consequence relation in terms of a monotonic logic or in terms of a semantics or in terms of continuations of a proof. And as a logic may be decidable for certain fragments of the language, there may also be criteria for derivability.

A general characteristic of the consequence relations mentioned in the previous section is that certain inferences are considered as correct iff certain formulas behave normally. What normality means will depend on the adaptive logic. In an inconsistency-adaptive logic, abnormalities are inconsistencies (possibly of a specific form); in some adaptive logics of induction, abnormalities are negations of generalizations (for example: ~( x)(Px

x)(Px Qx)). In some (prioritized) adaptive logics, abnormalities (of some priority level) are negations of premises (of that priority) — see the section on Flat and prioritized adaptive logics for an example.

Qx)). In some (prioritized) adaptive logics, abnormalities (of some priority level) are negations of premises (of that priority) — see the section on Flat and prioritized adaptive logics for an example.

An adaptive logic supposes that all formulas behave normally unless and until proven otherwise. Moreover, if an abnormality occurs, it is considered as local. This means that, even if some formula behaves abnormally, all other formulas are still supposed to behave normally unless and until proven otherwise. We shall see the effect of this in the following section.

While some consequences of a set of premises depend on the normal behaviour of certain formulas, other consequences follow come what may. Thus, an adaptive logic of induction enables one to derive certain generalizations as well as certain ‘predictions’ from a set of premises. To do so, one relies on the supposition that formulas behave normally unless and until proven otherwise. However, the premises also have deductive consequences that follow independently of any normality suppositions.

This naturally leads to seeing an adaptive logic as defined by three elements: the lower limit logic, a set of abnormalities, and an adaptive strategy.

· The lower limit logic determines which consequences hold independently of any presuppositions (or conditions).

· A set of abnormalities, which is characterized by a logical form. For example, the set of abnormalities may contain the existential closure of all formulas of the form A&~A. This logical form may be restricted. For example, the formulas of the form A&~A may be restricted to those in which A is a primitive formula (a schematic letter for sentences, a primitive predicative formula, or an identity). Extending the lower limit logic with an axiom that rules out the occurrence of abnormalities, results in the upper limit logic. In other words, the set of lower limit models that verify no abnormality are the upper limit models. The upper limit logic determines which consequences follow in the normal situation.

· An adaptive strategy. If an abnormality is derivable from the premises (by the lower limit logic), the upper limit logic reduces the premises (or theory) to triviality. However, the adaptive logic still interprets the premises “as normally as possible”. This phrase is ambiguous: there are several ways to do so. The adaptive strategy will pick one specific way to interpret the premises as normally as possible.

This clarifies the way in which adaptive logics adapt themselves to specific premises. The logic interprets the premises in agreement with the lower limit logic and, moreover, as much as possible in agreement with the upper limit logic. If some formulas (premises or lower limit consequences of the premises) are abnormal, the adaptive logic will not add the upper limit consequences of these formulas.

(Universiteit Gent, Centre for Logic and Philosophy of Science)

http://logica.ugent.be/adlog/al.html

Maggio 23, 2025

On Having Survived the Academic Moral Philosophy of the 20th Century. Alasdair MacIntyre (1929-2025)

I was already fifty-five years old when I discovered that I had become a Thomistic Aristotelian. But I had first encountered Thomism thirty-eight years earlier, as an undergraduate, not in the form of moral philosophy, but in that of a critique of English culture developed by members of the Dominican order. Yet, although impressed by that critique, I hesitated, for those Dominicans made me aware of the philosophical presuppositions of their critique, of a set of Thomistic judgments about the relationships between body, mind, and soul, about passions, will, and intellect, about virtues and reason-informed human actions. And those theses I found problematic. Why so?

From 1945 to 1949 I was an undergraduate student in classics at what was then Queen Mary College in the University of London, reading Greek texts of Plato and Aristotle with my teachers, while also, from 1947 onwards, occasionally attending lectures given by A. J. Ayer or Karl Popper, or by visiting speakers to Ayer’s seminar at University College, such as John Wisdom. Early on I had read Language, Truth and Logic, and Ayer’s student James Thomson introduced me to the Tractatus and to Tarski’s work on truth. Ayer and his students were exemplary in their clarity and rigor and in the philosophical excitement that their debates generated. And I became convinced that the test of any set of philosophical theses, including those defended by Thomists, was whether it could be vindicated. In and through such debates. Yet I also had to learn—and this took a little longer—that in the debates of academic philosophy in the twentieth century no set of theses is ever decisively vindicated.

Maggio 22, 2025

Maggio 21, 2025

Maggio 10, 2025

Italo Calvino. I livelli della realtà

L’opera letteraria potrebbe essere definita come un’operazione nel linguaggio scritto che coinvolge contemporaneamente più livelli di realtà.

… la letteratura non conosce la realtà ma solo livelli. Se esista la realtà di cui i vari livelli non sono che aspetti parziali, o se esistano solo i livelli, questo la letteratura non può deciderlo. La letteratura conosce la realtà dei livelli e questa è una realtà che conosce forse meglio di quanto non s’arrivi a conoscerla attraverso altri procedimenti conoscitivi. È già molto.

(I livelli della realtà in letteratura. 1978)

Maggio 6, 2025

Aprile 24, 2025

I should have loved biology too

One of the stories in the book, the discovery of the gene that caused Huntington’s disease, moved me tremendously when I first read it a few years ago. It’s the perfect example of the amount of effort that goes into a scientific discovery that then ends up as a single sentence in a textbook; in this case, that Huntington’s disease is a hereditary, neurodegenerative disorder caused by a mutation in a single gene.

The story of finding that mutation would make a thrilling movie: a young woman named Nancy Wexler, devastated by the news that her mother has been diagnosed with Huntignton’s and that she and her sister would have a 50-50 chance of getting it, decides to devote her life to solving this medical mystery. Her quest takes her from nursing homes in Los Angeles to interdisciplinary scientific workshops in Boston to stilt villages surrounding Lake Maracaibo in Venezuela. Her decade-long blood and skin sample collection efforts there would create the largest family tree with Huntington’s, leading to the first genetic test for the disease, followed by locating the precise genetic mutation that caused it.

The gene sequence had a strange repeating structure, CAGCAGCAG… continuing for 17 repeats on average (ranging between 10 to 35 normally), encoding a huge protein that’s found in neurons and testicular tissue (its exact function is still not well understood). The mutation that causes HD increases the number of repeats to more than forty – a “molecular stutter” – creating a longer huntingtin protein, which is believed to form abnormally sized clumps when enzymes in neural cells cut it. The more repeats there are, the sooner the symptoms occur and the higher the severity.

Nancy herself opted not to take the genetic test she helped create. “If the test showed I have the gene,” she wrote in 1991, “would I continue to feel the happiness, the passion, the occasional ecstasy I feel now? Is the chance of release from Huntington’s worth the risk of losing joy?”. In 2020, at the age of 74, she revealed that she had Huntington’s. The public acknowledgment was not a surprise for those close to her – for the last decade, they noticed her gait slowly deteriorate, speech slur, and limbs jerk in random directions, the same characteristics she saw in her mother half a century ago, and in the hundreds of Venezuelan patients she tended to ever since.

The more you explore, the more astonishing it gets. Suddenly, you’re surrounded by these facts that stop you in your tracks. Like the fact that there are 20-30 trillion red blood cells in our body, making up roughly 84% of all our cells, and 1.2 million are created in our bone marrow every second. Or the fact that our visual system is predictive, calculating where to move the hand to catch a ball before your visual system has fully registered its trajectory.

One of my favorite ‘sentences that stopped me in my tracks’ comes from Nick Lane’s book, The Vital Question. He starts with carefully explaining that all cells derive their energy from a single type of chemical reaction, the redox reaction, where electrons are transferred from one molecule to another. Rust is a redox reaction: iron donates electrons to oxygen, being oxidized in the process. Same with fire: oxygen (O2) is reduced to water after receiving two electrons (O2-) and then two protons (H2O), balancing the charges, and releasing heat in the process. Respiration — the process that turns our food into energy — does exactly this as well, except that it conserves some of the energy in the form of a molecule called adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Think of ATP as an energy currency, able to be stored or converted back into energy by splitting the molecule into ADP (adenosine diphosphate) and Pi (phospate). And so, he writes, “in the end respiration and burning are equivalent; the slight delay in the middle is what we know as life.”

Nehal Udyavar

https://nehalslearnings.substack.com/p/i-should-have-loved-biology-too

Aprile 22, 2025

Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences

Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences is an invaluable resource for students, researchers, and curious readers. Its 465 essays by leading scholars highlight some of the most compelling topics in current scholarship, presented through an interdisciplinary lens. The essays are fully cross-referenced with hyperlinks that illuminate connections between seemingly disparate ideas, promoting interdisciplinary and multi-layered awareness on key topics.

Emerging Trends provides an opportunity for leading scholars to share their expertise, and for readers to understand how groundbreaking ideas will shape the trajectory of research in the coming decades. It focuses the five core social and behavioral science disciplines – Psychology, Social Psychology, Sociology and Political Science – with select entries in Anthropology, Economics, and Education, as well as immigration, technology, and media.

By posting Emerging Trends online alongside its own website, CASBS has made it openly accessible to any interested reader anywhere in the world. We hope it will be widely explored and used.

(Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University)

https://emergingtrends.stanford.edu/

Aprile 21, 2025

Sul linguaggio mentale. I ricordi post-ictus di una signora. What my stroke taught me

At this point I didn’t know much about my brain injury at all. I wasn’t in any pain, so my thoughts about my new condition were unfocused and fleeting. Instead of being occupied by questions about why I was in the hospital and what had happened to me, my mind was engrossed in an entirely different set of perceptions. The smallest of activities would enthrall me. Dressing myself, I was awed by the orbital distance between cloth and flesh. Brushing my teeth, I was enchanted by the stiffness of the bristles and the sponginess of my gums. I also spent an inordinate amount of time looking out the window. My view was mainly of the hospital’s rooftop, with its gray and untextured panels, though I developed a lot of interest in a nearby tree. I could only make out the tops of the branches, but I’d watch this section of needles and boughs intently, fascinated by how the slightest wind would change the shape entirely. It was always and never the same tree.

Very few things disturbed me during this period of time. But even in this formless daydream I remember the moment that most closely resembled real distress. Or, at least, when I became aware of an actual loss.

It must have been midday because the sunlight was falling across my body, and that slat of light emphasized the white nightstand on my left. My parents had filled the shelves inside with clothing, and the nurses made sure there were plenty of liquids for me to drink in there, too. On this day, I noticed that there was a stack of magazines on the nightstand, as well as a book. I am not sure how long they had been there—for all I knew, they could have even predated my arrival—but this was the first time they piqued my interest.

The high gloss of the magazine cover felt wet in my hands. And as I opened it up, I was instantly bombarded with photos of red carpet parades and illustrated makeup tips, a circus of color and distraction. I couldn’t linger anywhere. It felt as if the magazine were shouting at me. Closing it was a relief.

I turned to the book. It was a novel by Agatha Christie, something I had probably read many years earlier. I opened to Chapter One and flipped slowly and evenly through the first few pages, a motion that seemed to come naturally to me. But on the third page, I stopped. I returned to the first page and started again. Slower this time. Much slower. My eyes focused and refocused in the bright sunlight, but I continued to only see the black, blocked shapes where words used to be.

Thinking about it now, I don’t know how I could be so certain that it was an Agatha Christie novel, especially since this was the very moment I became aware I couldn’t read anymore. With this simultaneously familiar and unfamiliar book in my hands, I first took in the actual loss of words. For my entire life, language had been at the forefront of every personal or professional achievement, and very few things had brought me as much joy and purpose. If I had ever been warned that I might be robbed of my ability to read, even for a limited amount of time, it would have been a devastation too cruel to bear. Or so I would have thought. But a day did come when I couldn’t read the book in front of me, when paragraphs appeared to be nothing more than senseless jumbles, and the way I actually processed this massive loss was surprisingly mild. The knowledge of the failure was jarring, without a doubt, but was there any misery or angst? No. My reaction was much less sharp. A vague sense of disappointment swept through me, but then … my inability to use words in this way just felt like transient information. Now that the ability was gone, I could no longer think of how or why it should have any influence on my life whatsoever.

My trouble with spoken language was mirrored in my written language. I discovered as I progressed in my sessions with Anne that I had not completely forgotten the alphabet, but I had forgotten its order. If I isolated single letters at a time, I could still identify them on a page. It took a lot of guidance from Anne, but with her by my side, I could slowly sound out these letters, occasionally creating a very fragile word. Anne noted: “There are frequent errors reading aloud, especially words with irregular pronunciations, and Lauren finds it difficult to know if she is correct or not.” So, while I had not lost my ability to read entirely, “reading” in this new iteration of my life involved a razor-sharp focus, accommodating only a word at a time. I also wasn’t able to know my own accuracy without someone else’s support. I would slowly sound out a word, but it took so long that when I went on to tackle the next one, I often would forget what I had just read. Perhaps that was what had happened with the Agatha Christie book I had attempted to read by myself. I had been expecting the language on the page to behave the way it used to, and when it didn’t, the whole picture crumbled in front of me. Words could be approachable in small, isolated units. But a full sentence? That was beyond imagining.

The rupture had originated on the middle cerebral artery in the left hemisphere of my brain, bleeding into the Sylvian fissures and my left basal ganglia. This cerebral artery supplies the blood for the two language centers of the brain—Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area. The basal ganglia are usually associated with motor control, but they also affect habits, cognition, and emotion. Some basal injuries can blunt emotional awareness and slow “goal-directed” activity. With such a wide range of influences, the alterations to the basal ganglia were probably affecting me in many ways at the time, but after the rupture, it was my faltering language that was my most visible symptom.

(Lauren Marks)