Giugno 30, 2025

Giugno 25, 2025

The worthwhile problems are the ones you can really solve. Da una lettera di Richard Feynman

Dear Koichi,

I was very happy to hear from you, and that you have such a position in the Research Laboratories. Unfortunately your letter made me unhappy for you seem to be truly sad. It seems that the influence of your teacher has been to give you a false idea of what are worthwhile problems. The worthwhile problems are the ones you can really solve or help solve, the ones you can really contribute something to. A problem is grand in science if it lies before us unsolved and we see some way for us to make some headway into it. I would advise you to take even simpler, or as you say, humbler, problems until you find some you can really solve easily, no matter how trivial. You will get the pleasure of success, and of helping your fellow man, even if it is only to answer a question in the mind of a colleague less able than you. You must not take away from yourself these pleasures because you have some erroneous idea of what is worthwhile.

You met me at the peak of my career when I seemed to you to be concerned with problems close to the gods. But at the same time I had another Ph.D. Student (Albert Hibbs) was on how it is that the winds build up waves blowing over water in the sea. I accepted him as a student because he came to me with the problem he wanted to solve. With you I made a mistake, I gave you the problem instead of letting you find your own; and left you with a wrong idea of what is interesting or pleasant or important to work on (namely those problems you see you may do something about). I am sorry, excuse me. I hope by this letter to correct it a little.

I have worked on innumerable problems that you would call humble, but which I enjoyed and felt very good about because I sometimes could partially succeed. For example, experiments on the coefficient of friction on highly polished surfaces, to try to learn something about how friction worked (failure). Or, how elastic properties of crystals depends on the forces between the atoms in them, or how to make electroplated metal stick to plastic objects (like radio knobs). Or, how neutrons diffuse out of Uranium. Or, the reflection of electromagnetic waves from films coating glass. The development of shock waves in explosions. The design of a neutron counter. Why some elements capture electrons from the L-orbits, but not the K-orbits. General theory of how to fold paper to make a certain type of child’s toy (called flexagons). The energy levels in the light nuclei. The theory of turbulence (I have spent several years on it without success). Plus all the “grander” problems of quantum theory.

No problem is too small or too trivial if we can really do something about it.

You say you are a nameless man. You are not to your wife and to your child. You will not long remain so to your immediate colleagues if you can answer their simple questions when they come into your office. You are not nameless to me. Do not remain nameless to yourself – it is too sad a way to be. now your place in the world and evaluate yourself fairly, not in terms of your naïve ideals of your own youth, nor in terms of what you erroneously imagine your teacher’s ideals are.

Best of luck and happiness. Sincerely, Richard P. Feynman.

http://genius.cat-v.org/richard-feynman/writtings/letters/problems

Giugno 23, 2025

L’Orlando furioso. Le penne e i destrieri

La bella donna tuttavolta priega

ch’invan la dura squama oltre non pesti.

— Torna, per Dio, signor: prima mi slega

(dicea piangendo), che l’orca si desti:

portami teco e in mezzo il mar mi anniega:

non far ch’in ventre al brutto pesce io resti. —

Ruggier, commosso dunque al giusto grido,

slegò la donna, e la levò dal lido.

(…)

Quivi il bramoso cavallier ritenne

l’audace corso, e nel pratel discese;

e fe’ raccorre al suo destrier le penne,

ma non a tal che piú le avea distese.

Del destrier sceso, a pena si ritenne

di salir altri; ma tennel l’arnese:

l’arnese il tenne, che bisognò trarre,

e contra il suo disir messe le sbarre.

Frettoloso, or da questo or da quel canto

confusamente l’arme si levava.

Non gli parve altra volta mai star tanto;

che s’un laccio sciogliea, dui n’annodava.

Ma troppo è lungo ormai, Signor, il canto,

e forse ch’anco l’ascoltar vi grava:

si ch’io differirò l’istoria mia

in altro tempo che piú grata sia.

Orlando furioso. Canto X. 111-115.

Giugno 15, 2025

Giugno 12, 2025

La solitudine

La solitudine – a volerla debitamente definire – è di tre tipi: del luogo …; del tempo, ovverosia delle notti, quando anche nel foro c’è solitudine e silenzio; dell’animo, ovverosia di quelli che, per la straordinaria capacità di concentrarsi nella contemplazione, si sottraggono al mezzogiorno e alla piazza affollata e ignorano che cosa vi succeda e sono soli in qualunque momento e luogo vogliano esserlo. (…)

Francesco Petrarca. De vita solitaria.

Giugno 11, 2025

Natural Semantic Metalanguage (NSM)

The Natural Semantic Metalanguage approach, originated by Anna Wierzbicka, can lay claim to being the most well-developed, comprehensive and practical approach to cross-linguistic and cross-cultural semantics on the contemporary scene. It has been applied to over 30 languages from many parts of the world.

The NSM approach is based on evidence that there is a small core of basic, universal meanings, known as semantic primes, which can be expressed by words or other linguistic expressions in all languages. This common core of meaning can be used as a tool for linguistic and cultural analysis: to explain the meanings of complex and culture-specific words and grammatical constructions (using semantic explications), and to articulate culture-specific values and attitudes (using cultural scripts). The theory also provides a semantic foundation for universal grammar and for linguistic typology.

Using NSM allows us to formulate analyses which are clear, precise, cross-translatable, non-Anglocentric, and intelligible to people without specialist linguistic training.

The method has applications in intercultural communication, lexicography (dictionary making), language teaching, the study of child language acquisition, legal semantics, and other areas.

(Griffith University)

https://intranet.secure.griffith.edu.au/schools-departments/natural-semantic-metalanguage

Giugno 3, 2025

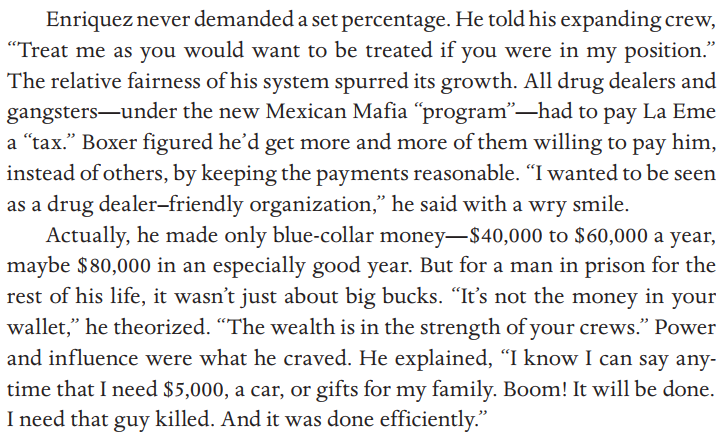

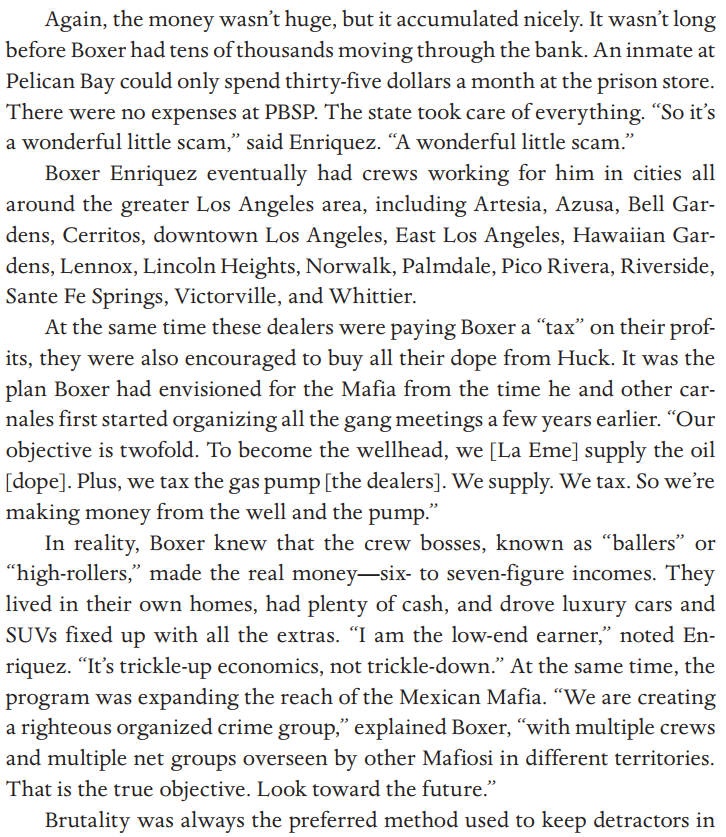

Trickle up economics. La mafia penitenziaria

The Black Hand: The Bloody Rise and Redemption of “Boxer” Enriquez, a Mexican Mob Killer. Chris Blatchford (2009)